I selected this blog post to highlight because Megan and I actually chose the same scene to analyze from The Dispossessed and I really love hearing her perspective. I’m not sure if I totally agree with the sentiment that Urras is representative of the United States and Anarres was representative of the Soviet Union (I think these worlds were definitely influenced by the Cold War but I don’t see the direct parallel in a lot of American novels as opposed to ones from the USSR which I find a lot more explicit) but I love the way Megan analyzed “nightmare street” through Shevek’s character and also drew comparisons to our own society.

Megan Barber 11/9

The term “cognitive estrangement” comes from Darko Suvin’s book, Metamorphoses of Science Fiction, where Suvin describes it as the idea of taking a familiar concept to the reader and placing it in a science fiction world which makes the concept appear completely alien at first glance. The goal is usually to provoke introspection in the reader, either about themselves or their society, as the unique setting defamiliarizes the familiar and provides a fresh perspective. Suvin states, “ As used here, this term does not imply only a reflecting of but also on reality. It implies a creative approach tending toward a dynamic transformation rather than toward a static mirroring of the author’s environment” (Suvin 120).

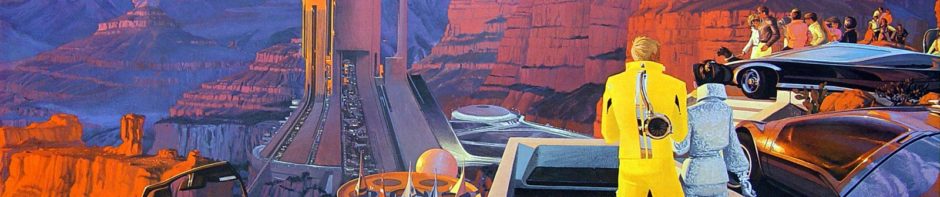

In Ursula Le Guin’s novel, The Dispossessed, the setting is immensely important as Urras and Anarres are clearly meant to reflect the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War era. The two planets are opposites in every sense of the word, Urras is primarily a capitalist planet with a rigid social hierarchy while Anarres is an anarchistic/socialist state where everyone is considered equal. The main character Shevek is a physicist from Anarres who travels to Urras in order to publish a new theory he has been working on. The events of the story are shown through Shevek’s eyes, which provides the reader with an interesting perspective on Urrsatsi culture. When Shevek comes to Urras he lives in a country known as A-Io, a place that would seem very familiar to American audiences with its capitalist economy, division of social classes, and obsession with material items. However, Le Guin introduces this world through an Anarresetsi lens, which makes these deeply ingrained facets of Urrsatsi/American society seem strange and even scary at times. During his second week in A-Io, Shevek is taken to a shopping district in Nio Esseia where he becomes extremely overwhelmed, even disgusted, by the concept of buying and selling goods. HE states, “And the strangest thing about the nightmare street was that none of the millions of things for sale were made there. They were only sold there. Where were the workshops, the factories, where were the farmers, the craftsmen, the miners, the weavers, the chemists, the carvers, the dyers, the designers, the machinists, where were the hands, the people who made? Out of sight, somewhere else. All the people in the shops were either buyers or sellers. They had no relation to the things but that of possession” (Le Guin 132). As Americans living in a society with a capitalist economy, this is not a strange concept to us. The expectation is that any goods you purchase were likely mass produced in a factory somewhere. When something is actually handmade it’s a pleasant surprise. Looking at this through Shevek’s eyes it’s horrifying how these goods only came to be as the result of a massive amount of work from various craftsmen, people who don’t receive any recognition for their work. By describing the shopping district through Shevek’s eyes, it defamiliarizes an everyday experience in the life of a person living under a capitalist economy. When you grow up in a world where this is a normal occurrence, it becomes incredibly difficult for you to think beyond the surface, about the greedy desire to own expensive objects just for the sake of owning them, to buy goods that were created by individuals who will get no credit for their craftsmanship, or to buy these items instead of using that money to help others. At one point Shevek remarks that an 8,400 unit coat is equal to 4 times the amount of money that constitutes a living wage. This critique on capitalism, and as individuals our need to display our status through material objects, is shown by providing a foreign perspective on familiar concepts.